2014-ben a New York-i El Museo del Barrio falai között láttam először átfogó kiállítást Marisol munkáiból – akkor még élt a művész. Marina Pacini kurátor kronologikus rendben vezette végig az életművet, finoman kibontva egy rendkívül összetett és következetes alkotói pályát. A mostani, koppenhágai Louisiana Múzeum által rendezett első európai nagyszabású Marisol-tárlat azonban más hangsúlyt választ: itt nem az időrenden, hanem a művész radikalizmusán van a fókusz.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Marisol művészete azért radikális, mert sem a klasszikus pop art kényelmes, csillogó felszíneihez, sem a korszak női szerepekről alkotott elvárásaihoz nem illeszkedik pontosan. Szobrai, bár első látásra könnyűnek és banálisnak mutatják magukat, tele vannak egzisztenciális kérdésekkel és politikai üzenetekkel, következetesen lebontják a beidegződött nemi szerepmintákat, és szembesítenek az egyenlőség törékenységével.

A dekoratív jelleg mögött mindig súlyos kérdések húzódnak meg, Marisolnál a test mindig politikai tér: durva fába vágott, festett, gipszlenyomatokkal és talált elemekkel kiegészített figurái a sérülékenység, a hatalom, az identitás és a társadalmi szerepek feszültségeit hordozzák. A humor és a groteszk nála fontos eszköz a világ abszurditásának leleplezésére.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

A termekben sétálva az az érzésünk, mintha mi magunk is belépnénk a sokaság közepébe. A groteszk, furcsa alakok társaságává válunk: egy vizuális tömeg részévé, amely egyszerre társadalomkritika és tükör. Marisol univerzuma nyugtalanító és színes, sötét és humoros, banális és rétegzett egyszerre. A humor és a báj itt nem menekülőút, hanem csapda: miközben közel engednek magukhoz, már bele is húznak minket azokba a kérdésekbe, amelyek elől nincs kibúvó.

A The Car például egy úton haladó autót ábrázol, tele utasokkal: a fejek egyszerű fából faragott formák, az arcok rajzok, fényképek és gipszmaszkok. Közelebbről megnézve kiderül, hogy az összes utas – a sofőrt kivéve – maga Marisol. A mű az önvizsgálathoz vezet: ki vagyok, hogyan látnak, hol a helyem. A Tea for Three fejei a venezuelai zászló színeire festett tömbön állnak. A nemzeti színek pátosza, a bohócszerű arcok és a groteszk testarányok együttese szatirikus képet rajzol a társadalomról: a zászló mint identitásszimbólum és a bohóc mint az emberi viselkedés karikatúrája itt összecsúszik. Ez a mű is jó példa arra, hogy Marisol finom, mégis kegyetlen humorral mutatja meg, mennyire törékenyek és abszurdak azok a szerepek és konstrukciók, amelyek mentén közösségeket, nemzeteket, sőt önmagunkat is értelmezzük.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

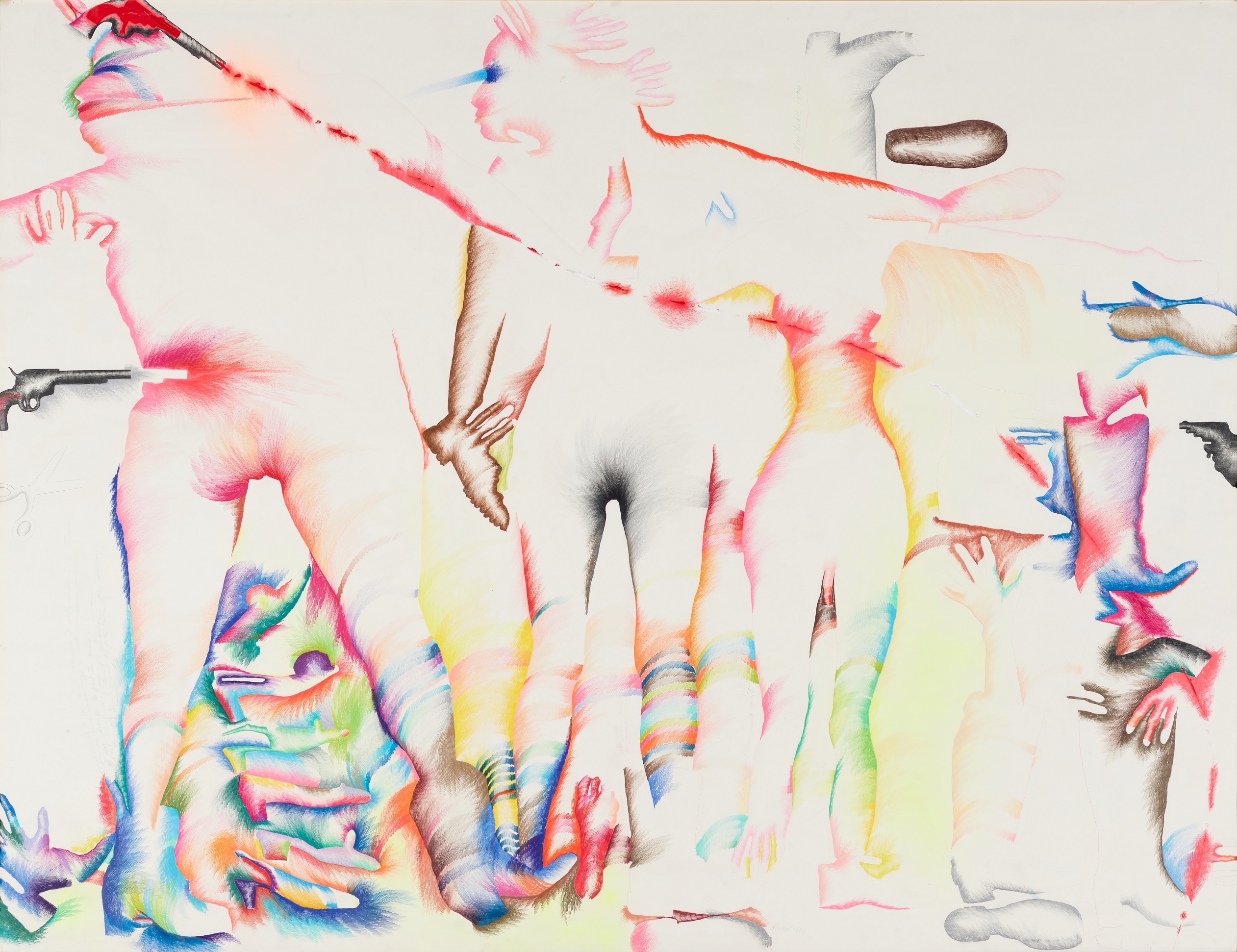

A kiállítás világosan megmutatja, hogy Marisol művészete egyszerre személyes és társadalmi. Egy helyen a saját testéről készített fragmentumokat egy nagy installációba rendezve jelennek meg azok a kérdések, amelyek a hetvenes évek feminista diskurzusát is foglalkoztatták: szexualitás, erotika, terhesség, a női test tárgyiasítása, erőszak. Rajzain testkontúrok, személyes vallomások, fragmentumok jelennek meg. Ezek a zavarbaejtő művek azt sugallják, hogy identitásunk nem rögzített, hanem folyamatosan alakuló, mozgásban lévő konstrukció.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Radikalizmusa azonban nemcsak témaválasztásában, hanem anyaghasználatában is tetten érhető. A pop art sima, csillogó felületei helyett Marisol a tapintható anyagminőségeket hagyja érvényesülni: fa, festék, gipsz, talált tárgyak – ezek a művek teli vannak nyersességgel és durvasággal. Nem véletlen, hogy az 1970-es évektől, amikor a pop arttól elfordulva egyre nyíltabban politikai művészetet kezdett létrehozni, fokozatosan kiesett a kritika és a közönség kegyeiből, és szerepe hosszú időre kitörlődött a pop art kánonjából.

A kiállítás Marisol és Andy Warhol kapcsolatával is foglalkozik. Warhol Marisolról készített kísérleti filmje, valamint a venezuelai művész Paris Review munkája idézi ezt a viszonyt. Mindkettőjük művészete a hírességek kultusza, a nemi identitás és az önreprezentáció körül forgott – Warhol pedig őszinte csodálattal beszélt Marisolról, „az első csillogó lányművészként” emlegetve őt.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Az Underwater sorozat külön termet kapott. 1968-ban, pályája csúcsán Marisol a Velencei Biennálén képviselte Venezuelát, és ugyanebben az évben a kasseli Documenta mindössze négy női résztvevőjének egyike volt. A vietnámi háború politikai légköre elől Ázsiába utazott, majd Thaiföldön intenzív búvárképzésen vett részt. A víz alatt töltött időt „újjászületésként” élte meg. A teremben látható víz alatti fotók, filmek és a haltestekkel kombinált önarcképszerű szobrok az ember és természet egymásrautaltságát, valamint az amerikai katonai-ipari komplexum és az óceánok élővilága közötti feszültséget vizsgálják – jóval megelőzve a kortárs ökoművészet gondolkodásmódját.

✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

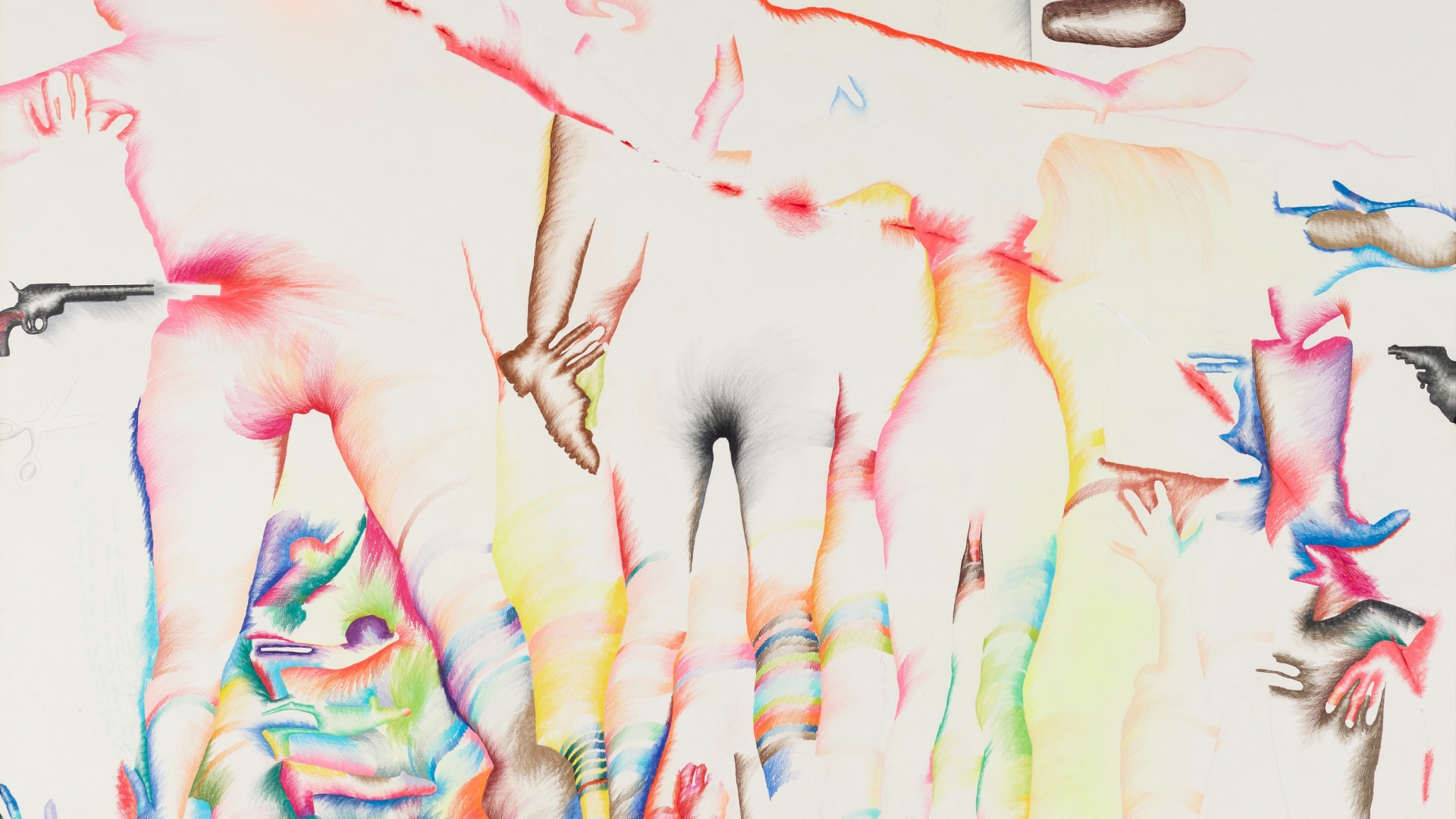

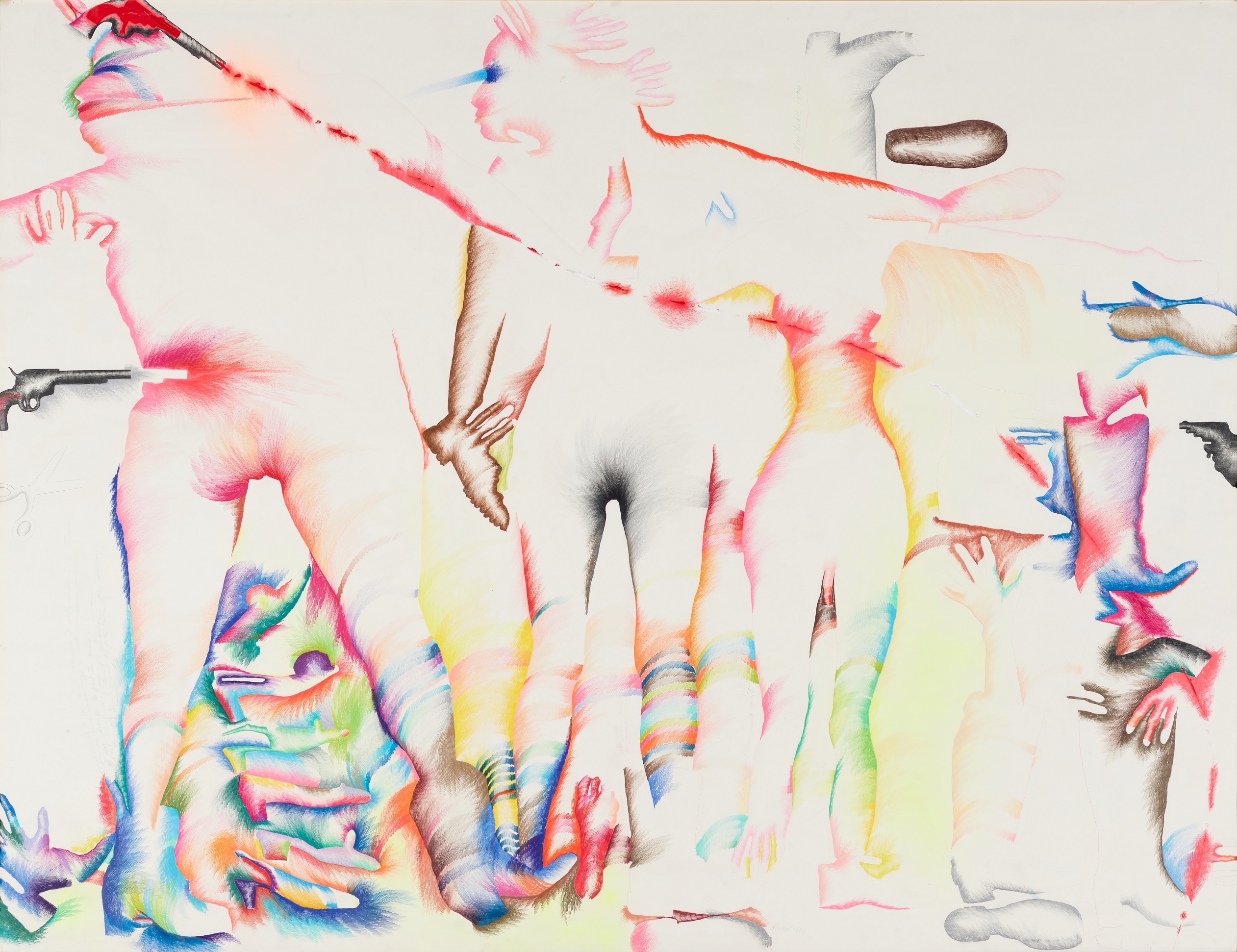

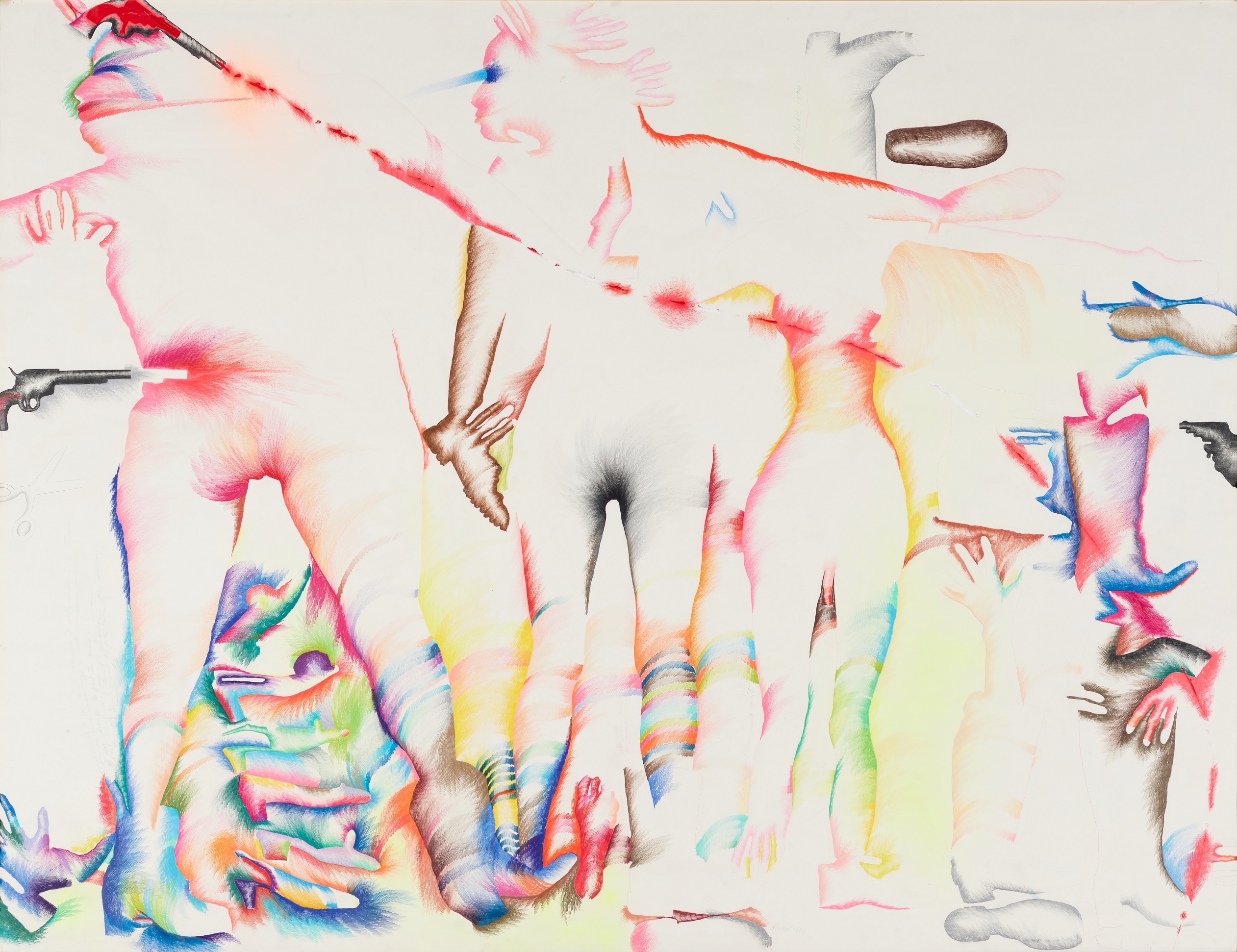

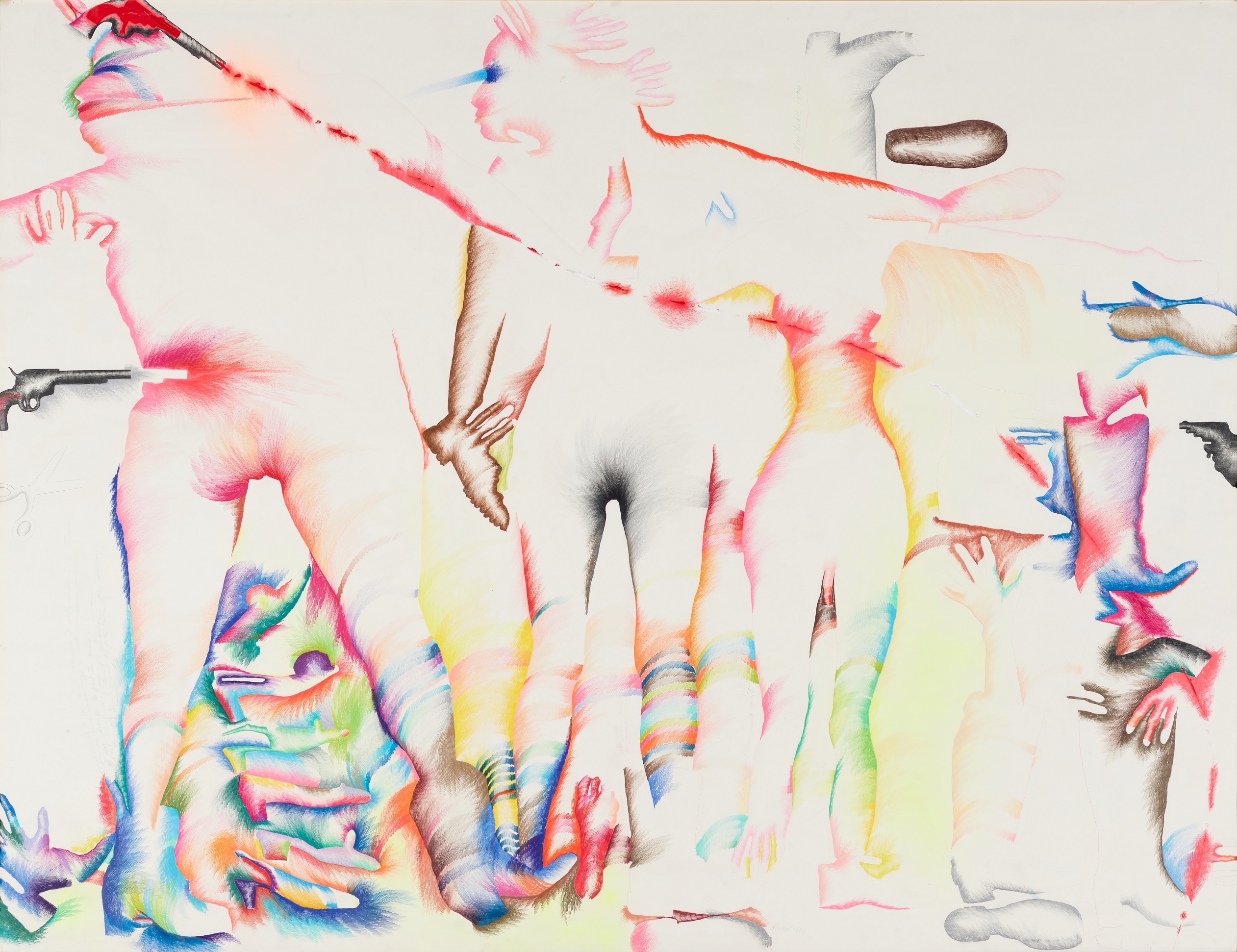

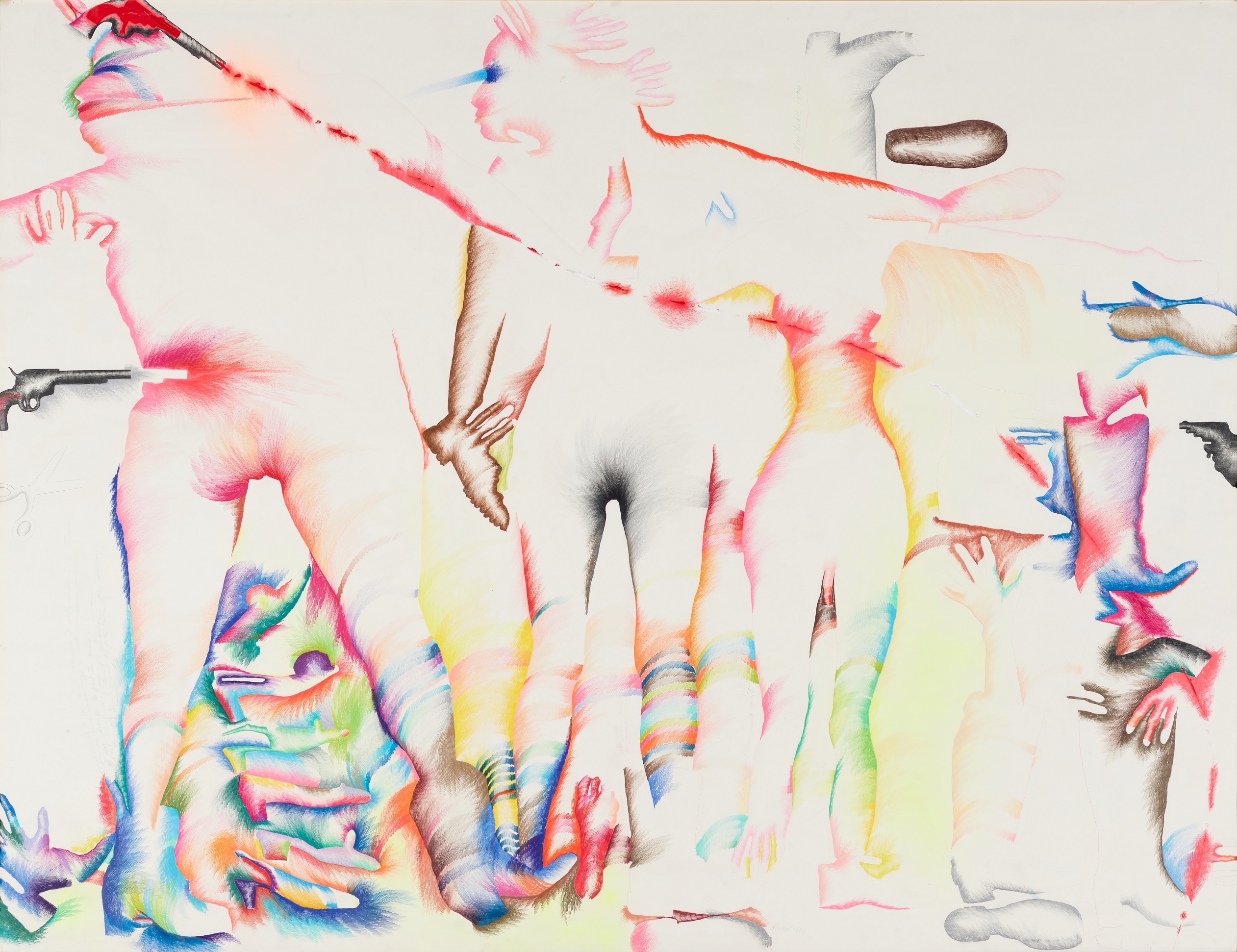

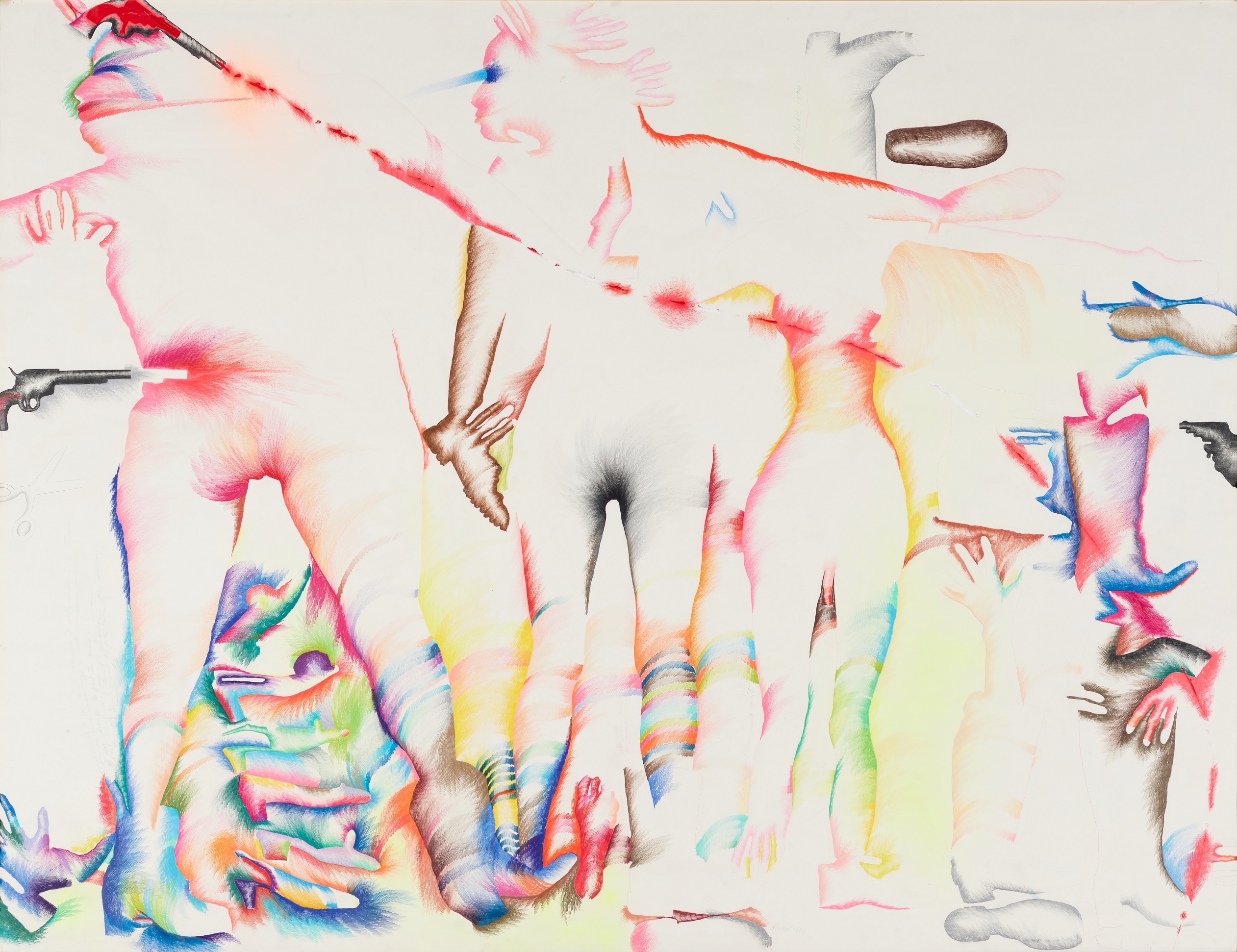

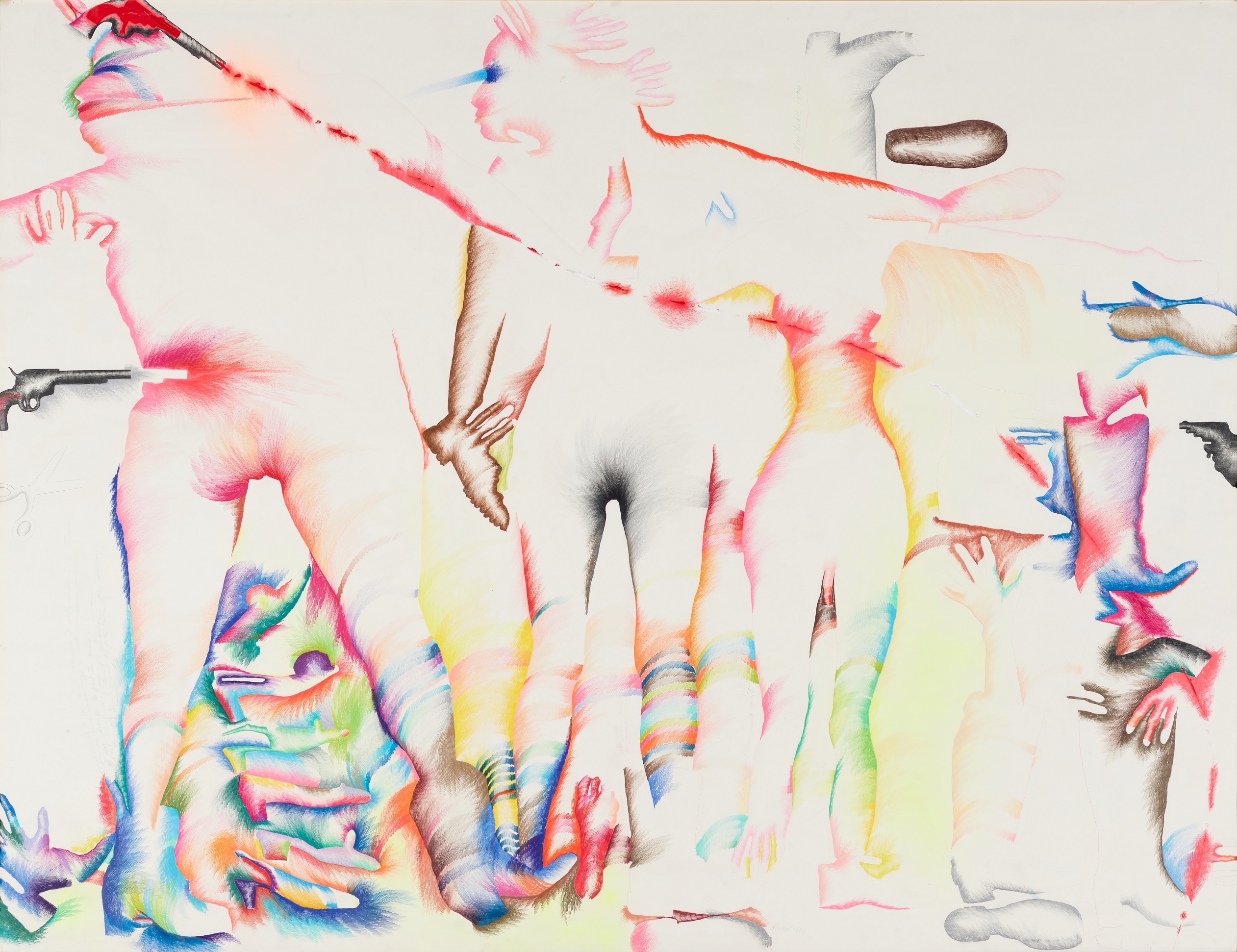

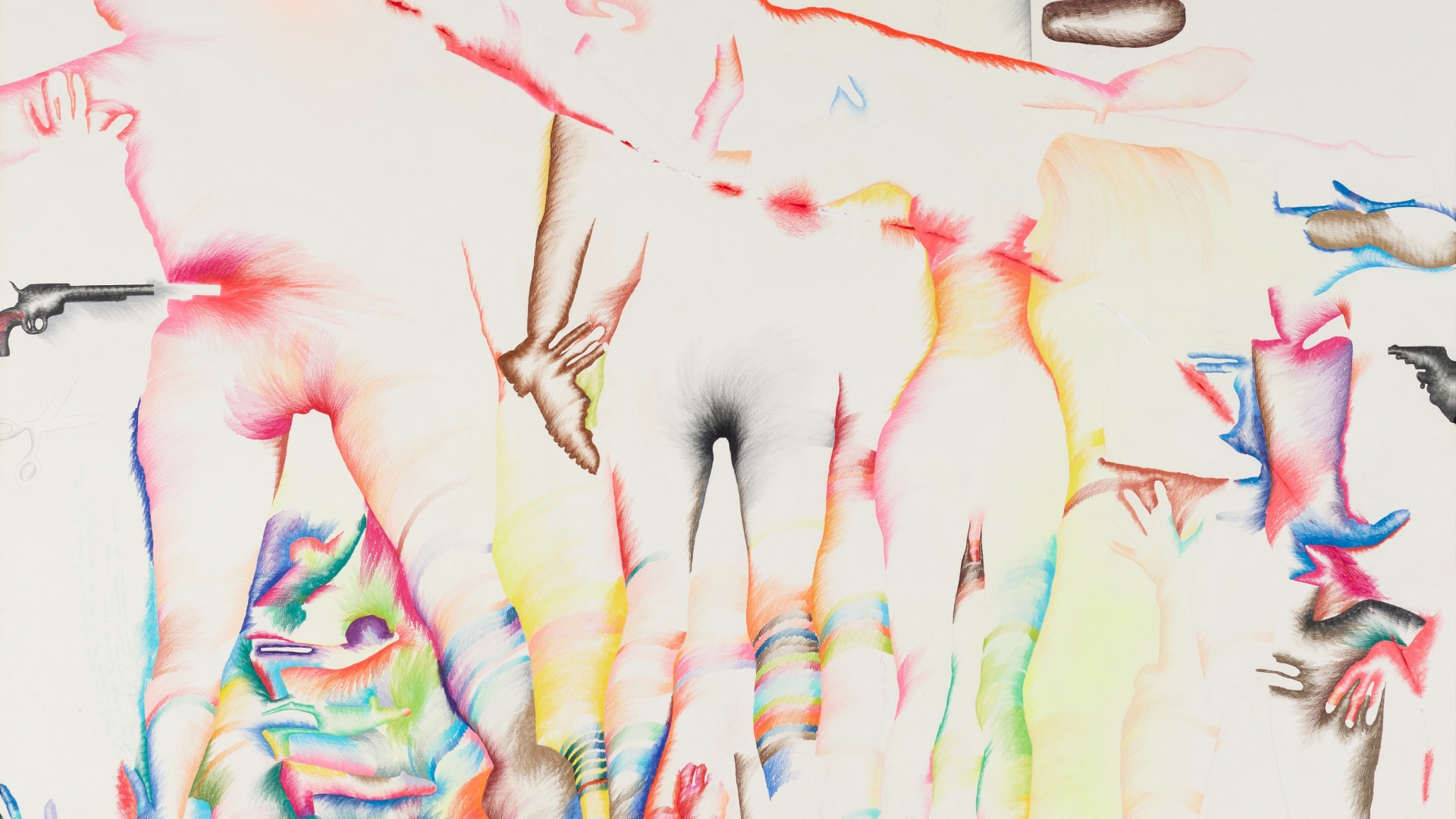

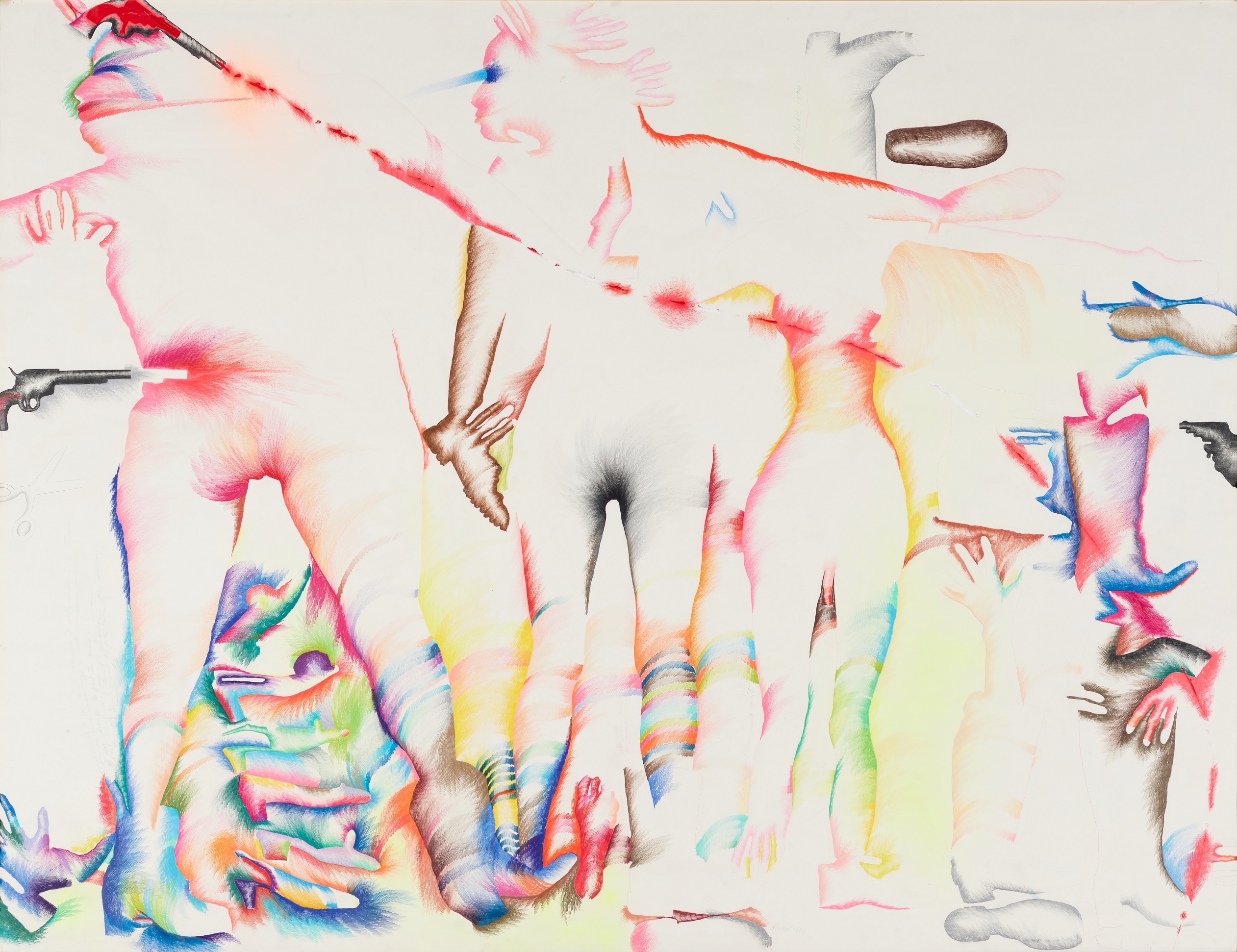

A tárlat egyik legnagyobb erénye, hogy nagy számban mutatja be Marisol rajzait is, amelyek az egész életművet áthatják. Ezek a vibráló, színes lapok az erotika felől közelítenek a testhez: a vágy itt nem direkt, hanem sejtelmes és töredezett, a test nem látvány, hanem tapasztalat, a vágy tere — egyszerre hívogató és elérhetetlen. Marisolnál az erotika nem privát ügy, hanem politikai gesztus: a test autonómiájának és az öröm jogának visszakövetelése egy erőszakos, férfiuralmi világban.

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art✕

AZ ÖSSZES KÉP: Részletek a Lousiana Museum Marisol c. kiállításából. Koppenhága, 2026.

© a Lousiana Museum jóvoltából. Foto: Camilla Stephan / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Ez a kiállítás nemcsak Marisol művészetét mutatja be, hanem azt is, mennyire előrelátó, radikális és ma is érvényes mindaz, amit a testről, a hatalomról, a politikáról és az ökológiáról gondolt. A Louisiana nem egyszerűen életművet állít ki, hanem újraír egy kánont. Az elmúlt évek amerikai tárlatai már elkezdték ezt a folyamatot, most pedig Koppenhágában válik világossá, mennyire súlyos és mennyire időszerű Marisol munkássága.

In 2014, I saw a comprehensive exhibition of Marisol’s work for the first time at New York’s El Museo del Barrio — the artist was still alive then. Curated by Marina Pacini, the show followed the oeuvre chronologically, unfolding a remarkably complex and coherent artistic trajectory. The current exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, the first major European retrospective of Marisol’s work, chooses a different emphasis: here the focus is not on chronology, but on the artist’s radicalism.

Marisol’s work is radical because it refuses to conform either to the comfortable, flat surfaces of Pop Art or to the prevailing expectations of women’s roles at the time. Her sculptures, though they may appear light or even banal at first glance, are filled with existential questions and political statements; they consistently dismantle ingrained gender norms and confront us with the fragility of equality. Beneath their decorative appearance lie weighty concerns. For Marisol, the body is always a political space: her figures — carved from rough wood, painted, and augmented with plaster casts and found objects — carry the tensions of vulnerability, power, identity, and social roles. Humor and the grotesque function not as relief, but as tools for exposing the absurdity of the world.

Walking through the galleries, one feels as if stepping directly into the crowd. We become companions to these grotesque, strange figures — part of a visual mass that is at once social critique and mirror. Marisol’s universe is unsettling and vibrant, dark and humorous, banal and layered at the same time. Here, charm and humor are not an escape but a trap: they draw us close only to pull us into questions from which there is no easy way out.

The Car, for example, depicts a vehicle traveling down a road, packed with passengers: the heads are simply carved wooden forms, the faces made of drawings, photographs, and plaster masks. On closer inspection, every passenger except the driver turns out to be Marisol herself. The work leads directly into self-examination: Who am I? How am I seen? Where is my place?

In Tea for Three, the heads rise from a block painted in the colors of the Venezuelan flag. The pathos of national symbolism, the clown-like faces, and the grotesque proportions together form a sharp satire of society: the flag as identity emblem and the clown as caricature of human behavior collapse into one. Once again, Marisol’s refined yet merciless humor reveals how fragile and absurd the roles and constructions are through which we understand communities, nations — and ourselves.

The exhibition makes clear that Marisol’s art is as personal as it is social. In one section, fragments cast from her own body are assembled into a large installation, engaging directly with questions central to 1970s feminist discourse: sexuality, eroticism, pregnancy, objectification of the female body, and violence. Her drawings feature body contours, personal confessions, and textual fragments. These unsettling works suggest that identity is not fixed, but a continuously evolving, mobile construction.

Her radicalism is equally evident in her material language. Instead of the smooth, glossy surfaces of Pop Art, Marisol foregrounds tactile matter: wood, paint, plaster, found objects — works dense with rawness and roughness. It is no coincidence that from the 1970s onward, as she turned increasingly toward overtly political art, she gradually fell out of critical favor and disappeared from the Pop Art canon for decades.

The exhibition also explores Marisol’s relationship with Andy Warhol. Warhol’s experimental films featuring Marisol, along with the Venezuelan artist’s contribution to The Paris Review, recall their close connection. Both artists revolved around celebrity culture, gender identity, and self-representation — and Warhol spoke of Marisol with genuine admiration, calling her “the first glamorous girl artist.”

The Underwater series occupies a dedicated gallery. In 1968, at the height of her career, Marisol represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale and was one of only four women among the 149 artists selected for Documenta in Kassel. Fleeing the political atmosphere of the Vietnam War, she traveled through Asia and undertook intensive scuba training in Thailand. She described her time underwater as a kind of rebirth. The underwater photographs, films, and self-portrait sculptures combined with fish bodies on view here explore the interdependence of humanity and nature, as well as the tension between the American military–industrial complex and marine life — anticipating the concerns of contemporary eco-art by decades.

One of the exhibition’s greatest strengths is the prominence given to Marisol’s drawings, which run like a thread through the entire oeuvre. These vibrant, colorful sheets approach the body through eroticism: desire is not direct but elusive and fragmented; the body is not an object of display but a field of experience, the terrain of desire — at once inviting and unreachable. For Marisol, eroticism is not a private matter but a political gesture: the reclaiming of bodily autonomy and the right to pleasure in a violent, patriarchal world.

This exhibition does more than present Marisol’s work; it reveals just how forward-thinking, radical, and urgent her ideas about the body, power, politics, and ecology remain today. The Louisiana does not simply present an oeuvre — it rewrites a canon. After years of American exhibitions initiating this process, Copenhagen now makes clear how consequential and how timely Marisol’s legacy truly is.